Sometimes rules exist more on paper than in practice, which could be an office dress code that only some people seem to follow, or a requirement to prioritize customer service that rarely seems to translate to customers being well-served. Or maybe it’s a parent who tells their child they “must be in bed by 8 p.m. every night” but routinely allows them to stay up later.

These unenforced rules seem like an obvious problem. At a minimum they suggest a lack of integrity or courage. Clearly, saying one thing and doing another is going to create some confusion at a minimum.

But I don’t think the simple solution to this problem—i.e. leadership should just be consistent—doesn’t really work. We could even say it obviously doesn’t work, because if it did, leaders would do it.

I think there is more going on here. And while we’ll spend some time going over specific consequences—including many you wouldn’t immediately think of—I’m going to make the case that when leadership fails to enforce legitimate rules, they may be doing so because it serves some important functions for the organization. Maybe not always, maybe not optimally, but in a way that provides some benefit.

Moreover, I believe that if we don’t understand and account for these functions, then any attempts to “fix” the hypocrisy or close the “gap” are at best going to fail, and at worst, hurt the organization more than it helps.

This phenomenon, which I call, “reserve authority,” or “strategic non-enforcement,”1 reflects a deeper tension in how groups collaborate: the need to balance stability and flexibility.

Strategic non-enforcement occurs when the leadership in organizations communicate clear rules or expectations, but complicity (though not necessarily consciously) choose not to enforce them. Far from being completely accidental, this ambiguity serves at least a few practical purposes. Let’s look at an example.

Example: “No Gifts to Clients”

Consider Sarah, a senior consultant at a firm with a clear “No Gifts to Clients” policy designed to avoid conflicts of interest. Despite the explicit policy, Sarah sends a small, thoughtful gift to smooth negotiations during a delicate client interaction.

Her manager, David, becomes aware but chooses not to enforce the policy strictly. David’s silence isn't negligence—it's strategic; even though he’s likely not consciously aware of it. He preserves the rule's existence while allowing situational flexibility that ultimately benefits client relationships and operational efficiency.

Some Important Nuance

It’s important to note that “strategic” doesn’t necessarily mean intentional or conscious. It just means that there are positive functions that it serves.

Also, “enforcement” doesn’t necessarily mean punishment. In fact, I use “enforce” quite broadly in my Structure System model, and it essentially means how effectively and humanely the system responds to violations. That could be a peer reminding another peer that they can’t send the contract to the client directly yet, because there is a policy that requires them to get the sign-off from a supervisor first. Or, someone reminding the facilitator that they skipped the required check-in round, rather than just remaining silent.

Again, it’s all about understanding how much the rules “matter” in that system—another intentionally broad term that is useful regardless of the type of collaborative system you are in.

1. What Does Strategic Non-Enforcement Do?

Obviously, we’ll look at the downsides and alternatives to the dynamic, but let’s first look at some positive functions it might serve.

Pragmatic Adaptation

Organizations may benefit from selective rule enforcement because it acknowledges the impracticality of monitoring every rule at all times. This approach creates a functional balance between the need for standardized expectations and the flexibility required to adapt to specific situations. By allowing localized discretion, the organization maintains overall coherence while remaining responsive and efficient.

Leadership Flexibility

Leaders may choose not to enforce certain rules because it preserves their flexibility to respond to changing circumstances without being constrained by rigid expectations. At the same time, selective enforcement reduces the administrative overhead of constant oversight, making leadership more efficient in practice, if not always more consistent.

Empowered Interpretation

For employees, inconsistent enforcement may feel empowering, offering space to exercise judgment and adapt to real-world complexity without the constant fear of punishment. It signals that while expectations exist, there’s room for interpretation and human fallibility. This grace fosters a more forgiving and realistic work environment.

In short, strategic non-enforcement may be the conventional organization’s way of maintaining a balance between stability and flexibility.

2. But at What Cost? Some Obvious (and Not-Obvious) Side-Effects of Strategic Non-Enforcement

Despite its practical advantages, strategic non-enforcement has some serious downsides. And some of the most damaging are the least obvious.

Erodes Trust

Selective enforcement often feels like hypocrisy. When some people are penalized and others aren’t, it creates a sense of favoritism. Even if unintentional, this damages credibility and makes peer accountability harder. Leaders who avoid difficult conversations in the name of flexibility weaken their own authority. In temporary groups, social dynamics might be enough—but long-term collaboration requires clear and shared expectations.

Incentivizes Ignorance

When leaders knowingly ignore rule violations, people take notice. It sets a precedent—like failing to defend a copyright, it erodes legitimacy. Employees stop surfacing issues because they assume the rules don’t really matter. Instead of being transparent, they stay quiet to protect themselves. This encourages secrecy over honesty and trains people to “parent-proof” their actions rather than engage in real accountability.

Shifts Blame Unfairly

When leadership avoids the work of consistent enforcement, that burden doesn’t disappear—it shifts. Employees are left to navigate unclear expectations and guess which rules actually count. They end up managing risk that leadership is no longer willing to hold. This creates stress, second-guessing, and a lingering sense that the system is unfair.

Undermines Collective Interest

Strategic ambiguity turns rule-following into a personal calculation. People stop thinking about what’s right for the group and start thinking about what they can get away with. Without clear connections between enforcement and shared purpose, opportunism replaces principle. The organization begins to lose its sense of collective responsibility.

Encourages Shadow Power

Inconsistent enforcement creates space for unearned influence. Leaders still decide when rules apply, which gives them quiet power to reward or punish as they see fit. Over time, authority shifts from formal structure to informal channels—charisma, favoritism, or persuasion behind the scenes. These shadow dynamics become entrenched, and power starts to operate without accountability.

3. So What Do We Do About It?

With the pros and cons out on the table, we can now ask the critical question: If strategic non-enforcement offers flexibility, efficiency, and empowerment—but only by trading away trust, fairness, and coherence—then how can we design systems that provide those benefits without paying such a steep price?

As I said in the beginning, most attempts to “fix” the problem or close the “gap” between what leaders say and what they enforce may hurt the organization more than it helps.

Too often the solutions are to fix the leaders, or fix the employees (with newer and seemingly “innovative” approaches being to fix both!)

Or, you can use a framework like Holacracy, while great in many ways, is also a huge commitment. It goes about solving this problem by fundamentally reshaping how power and authority work in the organization. That’s a big ask. And there are other options.

In contrast, my approach is to think in terms of structures—that is, look at how the group can leverage explicit, binding, and meaningful expectations as a way to reduce the likelihood that the shadow-parts will negatively impact its collaboration. And it can do this without having to distribute any power. Meaning, one advantage of this “structure-oriented” approach is that it integrates perfectly with Holacracy, but it also doesn’t require it.

Additionally, while it doesn’t require people to get “fixed” first in order for things to improve, it takes advantage of any capacity the human beings bring to it. Meaning, the significant side-effect of this structure-oriented approach is that people are more likely to learn and grow as a result.

Here are three alternative solutions for finding a healthier balance of stability and flexibility.

4. Three Ways to do What Strategic Non-Enforcement Does Without the Downsides

Pedantry and mastery are opposite attitudes toward rules. To apply a rule to the letter, rigidly, unquestioningly, in cases where it fits and in cases where it does not fit, is pedantry [...] To apply a rule with natural ease, with judgment, noticing the cases where it fits, and without ever letting the words of the rule obscure the purpose of the action or the opportunities of the situation, is mastery." -George Pólya, How to Solve It (1945)

A. Distinguish Guidelines from Rules

Remember the intent of strategic non-enforcement is to have clear and stable expectations, but also allow for a certain amount of local discretion. Well, as I wrote in my post about the four types of “rules,” there is one type that does this particularly well: “Guidelines.”

As a refresher, Guidelines...(which is just my label for this particular thing) “must be consciously considered; i.e., the person does not have the discretion to just ignore it, but at the same time, they retain the right to use their best judgment.” An example would be something like when a doctor must check if a patient has any known allergies before prescribing medication. The doctor isn’t required to act a specific way in every case—there may be exceptions or nuanced trade-offs—but they are expected to consciously consider the guideline and factor it into their decision-making, rather than ignore it altogether.

Normally, leaders only have two options—something is either a requirement, or it’s not. That binary distinction is important, but a Guideline provides precisely the kind of nuance that is needed in most knowledge-work collaboration today—it’s required, but leaves the final judgment up to the individual.

With all of this said, we still need to have firm requirements that people must honor (i.e. Rules or Laws) that don’t allow them much room for interpretation. But if you don’t make the distinction between these different types of expectations, then you’re likely making them less able to do what they’re supposed to do.

The precise details of how to properly use Guidelines is a novel and extremely important topic to cover, which I will get to in a future article, but here are a few quick examples of what they sound like:

Introducing a New Guideline (Manager sets a new requirement):

“Going forward, before approving any overtime for your teams, I want each of you to take a moment to consider if the overtime supports our quarterly priorities. I’ve already added a required box on the approval form, so you’ll still have discretion to approve it or not, but this formal reflection step is now part of the required process.”

Referencing the Guideline in Practice (Checking for consideration):

“I know we have a lot to deal with right now, but before we move forward with reallocating resources, I want to revisit the rule around considering cross-team impact. What kinds of effects have you thought about, or did you want to explore that together in this meeting?”

Enforcing After a Violation (Missed consideration with a response):

“We have a standing expectation that major client changes should include consideration of the contract terms. When you rolled this change out, what factors did you take into account?” [In response, the employee hesitates or admits they didn’t think about it.] “Well, that’s something we need to fix. I’m going to ask you to think about why you missed it and share with me one concrete action you’re going to take to ensure this doesn’t happen again.”

B. Look at the Whole “Structure System”

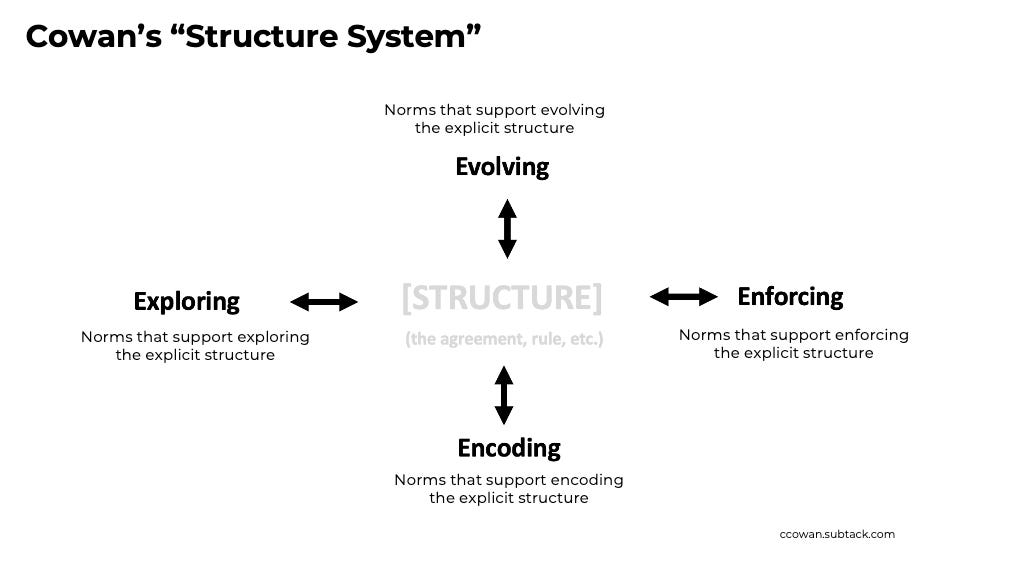

Using Guidelines goes a long way to striking a healthier balance between stability and flexibility, but it’s not enough. Ultimately what matters is a group’s structures or “rules” are generally perceived by the culture as something to be taken seriously and given respect. To do this well, I advocate that leaders think about the whole “structure system,” which can triangulate all of the relevant issues.

I’m not going to repeat the previous post on this topic, but I want to mention three particularly important considerations this model highlights.

i. Minimum Viable Structures:

Structures can’t matter if you have too many of them. And it would be unreasonable to expect leaders to monitor and regulate all of them. And yet, the implicit bias most structure systems have is to keep growing. Inevitably that means that they will include expectations that are out-of-date, irrelevant, or inaccurate. To improve the situation, organizations need to address issues like, “How can we reliably limit gunk from getting into the system (Exploring and Encoding aspects), and also have a reliable way of removing gunk from the system (Evolving aspect)?

Even just establishing term limits that trigger a revisiting of an expectation can help (e.g. “This is the policy for the next 6 months, and I’ll review it after that time to see if it needs to be changed.”) Holacracy, for example, also makes this easier by empowering each circle to self-govern through a tightly controlled governance process. Though again, you don’t need Holacracy’s version, but it helps to define some way to reduce the clutter.

ii. Turn Enforcing Into Reinforcing:

Most leaders in organizations seem to operate under an unexamined belief like, “If I have to enforce the rules all of the time, then employees will comply, but only because they don’t want to get in trouble. They won’t really understand and internalize them. If anything, if I consistently enforced the rules, I would only be disempowering them and limit their ability to make smart decisions for themselves.” And certainly there is some truth to the fact that structures can be used as an unhealthy crutch (see this article on Our Relationship to Rules and particularly the part about “Unhealthy Reliance.”)

But the assumption that you’re doing employees a disservice by doing your job of holding people accountable sounds more like a self-serving rationalization, than a representation of reality. In fact, human beings like being held accountable because it affirms that their actions matter. Here is a link to an article I wrote about the long research history that shows “challenge” and “support” are not mutually exclusive.

iii. Leaders Should Involve Employees, or Get More Involved Themselves

You know what makes employees more likely to follow an explicit expectation? If they had some hand (or the option of having a hand) in its creation and maintenance. For readers that know Holacracy, that system is great for this, but even in a conventional management hierarchy, even with the strictest of micro-managers, something in the structure system can always be adjusted to reduce the barriers employees normally have when rules are imposed upon them without their consent. Maybe it’s as simple as soliciting requests for exceptions. The point is, if the people impacted by the rule have no reliable pathways to be involved in defining the rules that bind them, nor can they propose changes or request reasonable exceptions, then their relational stance is predictably distant.

Or maybe that just doesn’t make sense. Maybe the people just need to fall in line and do what they are told. Hey, I can imagine scenarios where that makes perfect sense, so that might just be the reality. But if it is, don’t then pretend that somehow you’re also not responsible for the administrative costs that kind of approach is necessarily going to create. If you want to make yourself feel better, you can keep telling yourself acts of rebellion are the employee’s fault (or child’s, or volunteer’s) but that’s not going to make it any more true.

C. Embrace Rhetorical Influence (That is Anchored by Structures)

Finally, while I’m trying to make the case that strategic non-enforcement is a bad way of balancing stability and flexibility in a social system, I’m not saying it’s always bad. Delivering a statement, or communicating a command as a means of influencing others even in the absence of formal authority is essentially rhetoric or persuasion. Formal structures don’t eliminate the need for this inherently political realm, they just allow us to identify it more consistently.

In fact, I think it’s only bad when used within formalized collaborative contexts, simply because there are better ways of addressing the needs. But outside of that, just in regular life in which you don’t necessarily have any power or formal authority to impose an expectation and hold people to it, actually think it is extremely useful. And that’s because in those situations there is technically no binding rule you could enforce.

For example, a recent client where I was very direct and gave an “assignment” even though I am not leaning on my formal authority which requires them to accept assignments from me. They don’t. I have no such authority. Nothing close to it. They can completely ignore me if they so wish.

Yet, if I’m going to nudge them in the right direction and increase the odds of them taking my advice seriously, I can’t say “Hey…please do this even though I can’t make you do it…and I guess if you don’t want to do it, um….you don’t even have to. You don’t even technically need to listen to me now, so I guess I’m just asking you if you wouldn’t mind…and you won’t be violating any rules if you don’t, but I guess I’m still just asking if you could do it anyway.” That’s not a very convincing sales pitch.

Sometimes explicitly acknowledging that someone doesn’t have to follow your instructions may be useful, but generally it works just fine to lean on that assumption and your respect for their autonomy by just showing up how you think is best, such that you’re also completely receptive of their choice in how to respond to it. In this way, I consider this form of structuring to be rhetorical, not official. It is the primary default in a group, say if a group of friends are trying to come to an agreement about which movie to see.

But even in cases with clear power hierarchies, the rhetorical usage can be useful as long as both parties are sufficiently aware of the line between rhetoric and official authority.

5. Conclusion: Strategic Non-Enforcement Isn’t a Bug—It’s a Feature

If there’s one thing to take from all this, it’s that strategic non-enforcement isn’t necessarily a failure of leadership; it might be serving real, often unspoken needs. It likely helps organizations navigate the tension between structure and flexibility, and it emerges precisely because most systems lack better tools for doing so explicitly.

But just because it serves a purpose doesn’t mean it’s the best way to meet that purpose. The costs—erosion of trust, politicized enforcement, employee confusion—are often hidden until it’s too late.

But rather than doubling down on rigid compliance or retreating further into ambiguity, we can design smarter structures—like Guidelines and other elements of a well-tended structure system—that honor complexity without sacrificing clarity. We can recognize that rhetoric and persuasion still have their place, but they’re more powerful when grounded in systems that make expectations visible, revisable, and worth taking seriously.

For all of the complaining about leaders saying one thing and doing another, strategic non-enforcement didn’t show up by accident. I think it’s an adaptive response to real organizational constraints.

But if we can better understand what it’s doing, we’ll have the opportunity to evolve it into something better: a system where expectations are clear, local judgment is protected, and collaboration becomes more conscious and effective.

My concept of strategic non-enforcement shares similarities with the established academic construct of “constructive deviance” (Warren, 2003), where organizational norms or rules are intentionally violated by individuals to achieve positive outcomes. I didn’t know about that construct until after I came to my own conclusions, but I wanted to briefly acknowledge the similarities and differences. Both constructs recognize that departures from explicit rules can benefit organizational flexibility and adaptability. However, while Warren’s “constructive deviance” focuses primarily on employee-driven actions from the bottom-up, “reserve authority” or “strategic non-enforcement” highlights management's deliberate, though unconscious, use of ambiguity to achieve organizational goals. Said another way, “strategic non-enforcement” is what enables “constructive deviance,” and in my conceptualization is both much broader and deeper in its applications.

If this publication has been a source of wisdom for you then please consider helping me sustain it by becoming a monthly or annual contributor.

For just $8.00/month or $80.00/year, you'll help ensure I can continue dedicating more time to creating thoughtful, quality content. In fact, I’m currently sitting on over 200 draft articles (in various stages of development), which I just haven’t had time to publish. Of course, a third of those articles are probably crap, but that would still mean I’m sitting on tons of content I’d love to share.

As a sponsor, you’ll also be the first to receive future premium content, including a digital copy of my upcoming book, “The Proper Use of Shared Values.”

It’s completely optional and I’ll always provide as much content as I can for free, but your contributions will be critical for helping me spread the word about new ways of collaborating that are both more effective and more meaningful.

Thanks a lot! It has been a long read 😅

As a leader, I have been guilty of strategic non-enforcement - I realise now how this was in fact often detrimental 🙈

I like the three ways to (in part) remedy this. I feel they also have their downsides.

And I wonder if another concept from Holacracy could come in handy here as well: Individual Initiative.

The Holacracy constitution document says: "As a [member of the organisation], in some cases you are authorized to take Individual Initiative by acting beyond the authority of your Roles or by breaking rules in this Constitution."

https://www.holacracy.org/constitution/5-0/#art43

The text then goes on to describe the ins and outs of this.

One important point the text then makes is that you need to communicate about your own failure to comply with the established rules. So, in the above example of Sarah sending a gift to the client, she would be required to openly communicate: "Hey, I know we're not supposed to do this. And I believe that sending this small token of appreciation would not be seen as bribery (which is why we have this rule) because it is so minor."

The beauty I see in the concept of Individual Initiative is that it takes a lot of enforcement burden off leaders and also allows for every member in the organisation to take responsibility for their own actions.

So, I propose to add Individual Initiative as one habit that might even prevent strategic non-enforcement to happen. What do you think?