Titanic Myth: Someone is Always to Blame

An Important Lesson (that's not) About Personal Responsibility

The new-ish Netflix documentaries on the OceanGate submersible disaster sent me down a rabbit hole this week—specifically back into Titanic’s history.

The common narrative about the sinking of the Titanic goes something like this: it was man’s hubris. An arrogant captain ignoring iceberg warnings. A shipbuilder boasting about an “unsinkable” design. Wealthy elites more concerned with status than safety.

But the real story is messier. Yes, there were poor decisions and tragic oversights. But there were also systemic issues, communication breakdowns, conflicting incentives, and a technological confidence that was widespread—not isolated.

And in doing so, I was reminded of the human need to assign blame to someone. To personalize complex causes so that the universe feels fair and predictable. These myths of the failures of personal responsibility are comforting, but worth challenging. That’s what this article is about.

Because when we reduce systemic failures to the moral shortcomings of individuals, we blind ourselves to the structures that actually need fixing. And worse, we set ourselves up to repeat the same mistakes—just with different scapegoats.

The Refraction Theory

Now, the causes of Titanic’s sinking are multi-variant, so I also don’t want to perpetuate the myth of singular causation than I do the one about individual responsibility. Moreover, I am by no means and expert. Obviously.

But I have read books on the topic and one of the most compelling theories I’ve heard about what happened that night is rarely even mentioned: Tim Maltin’s refraction theory.

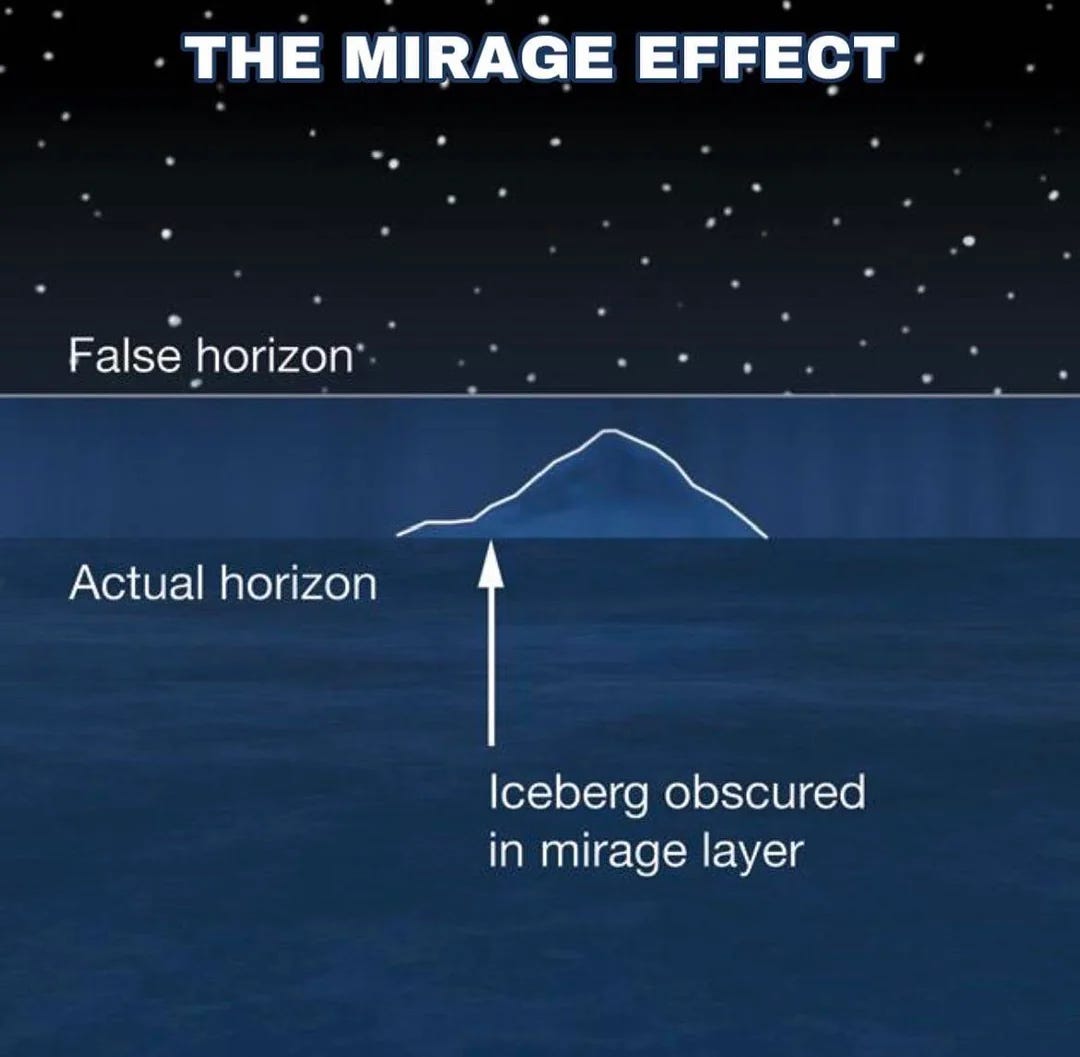

For those unfamiliar, Maltin proposes that a rare thermal inversion over the North Atlantic that night caused a super-refraction effect—bending light in such a way that it created a false horizon. The iceberg didn’t appear as a solid silhouette on the sea. Instead, it blended into a distorted haze just above the horizon line. In short, the iceberg couldn’t be seen in time, not because someone failed, but because nature played a trick that was effectively undetectable with 1912 eyes.

I find this theory persuasive—not just scientifically, but philosophically. Because it points to something we don’t like to admit: we are not in control. And when disaster strikes, we look for someone to blame—not always because they’re at fault, but because blame gives us a comforting illusion that tragedies only happen to those who make mistakes. If we can locate the flaw in their judgment, we can protect ourselves with better choices.

But Titanic’s real story doesn’t give us that clean arc.

Some Titanic Myths

A lot of the popular explanations for the disaster don’t hold up under scrutiny, but they persist because they feel emotionally satisfying.

Myth #1: They didn’t have enough lifeboats.

This one is practically universal—and wrong. First, the Titanic carried more lifeboats than legally required. Ships of the era weren’t expected to have enough lifeboats for everyone at once, because lifeboats were designed to ferry people to nearby rescue ships, not to evacuate an entire ship mid-ocean.

Second, more lifeboats wouldn’t have helped. Two lifeboats were still attached when the ship went down, and many others launched half-full. Even in the calmest sea, launching more boats would have required more time, more davits, more deck space, and more trained crew. There was simply no feasible scenario—especially not one that people in 1912 could have imagined—where double the number of lifeboats would have been usable before the ship sank.

Sure, in the abstract, having more lifeboats would have helped, in the same way as having an identical rescue ship following close behind the whole journey would have saved more lives too—but no one would suggest that was a practical or reasonable expectation. Citing lifeboat numbers as a cause of the disaster is not just misleading—it’s another scapegoat explanation that comforts more than it clarifies.

Myth #2: The lookouts didn’t have binoculars.

The popular belief is that if the lookouts had been given binoculars, they could have seen the iceberg in time to avoid disaster. The binoculars were, in fact, on board—locked in a cabinet. But the only man with the key, Second Officer David Blair, was reassigned before the voyage began. The theory goes that Captain Smith failed to ensure a proper handover, leaving the lookouts without access.

But even if this were true, it would be irrelevant. In 1912, binoculars weren’t helpful in low-light conditions, and would have narrowed the lookouts’ field of view. The naked eye was better suited for spotting large objects like icebergs, especially in the dark. The idea that binoculars would have made a difference is a myth that survives because it offers a tangible scapegoat—a forgotten key, a missed detail.

Myth #3: The Titanic was going too fast because of arrogance.

Admittedly, experts are a bit split on this, but I think there are compelling reasons to believe the Titanic’s Captain, Edward John Smith, wasn’t trying to set a speed record or have the ship arrive early.

First, she wasn’t the fastest ship afloat by a long way, and she was operating within normal cruising speeds for the time. The weather was clear, the sea was calm, and ice warnings were common—but rarely cause for alarm unless visibility was poor (and remember it actually seemed deceptively clear). Speed in the circumstance was likely a strategic necessity, precisely so that they could slow down if they really needed to and still be on schedule.

Second, despite how he is portrayed in James Cameron’s movie Titanic, J. Bruce Ismay, the managing director of the White Star Line who was aboard and ultimately escaped, did not want the ship to arrive too early for fear it would throw off the first-class passengers hotel reservations in New York.

Myth #4: The Californian’s captain was indifferent to distress signals.

The nearby ship, the Californian, saw Titanic’s signal flares but didn’t respond. It’s tempting to treat that as moral failure, but again, the truth is more complex. The same optical effects that hid the iceberg also distorted Titanic’s appearance, making it seem like a distant, unthreatening vessel. The wireless operator was asleep—not unusual for the time—and while we can say the California’s Captain should have investigated, it's more accurate to call it a reasoning error under ambiguity, not a failure of conscience. Today, ships are required to have 24-hour radio coverage as a direct reaction to this very case. And good example of how identifying procedural conditions, rather than assigning blame, led to significant safety improvements.

So What Really Happened?

Titanic sank because a series of ordinary decisions met an extraordinary situation. The conditions that night—the refraction, the darkness, the glancing blow instead of a head-on collision (which it would have survived)—combined into a moment no one was equipped to handle. There were no villains. Just people doing their jobs, operating under the assumptions of the time, caught in an event that exceeded imagination.

The real tragedy is not that people made bad choices. Though I’m sure some did. It’s that the world can sometimes produce outcomes that no one is prepared for, and afterward, we create myths that let us pretend we would have done better if we were in their shoes.

That’s not how the universe works. Control is always partial. And disasters are often made not by fools or cowards, but by good people operating under uncertainty.

So, sure, let’s learn what we can. And to do that we must scrutinize what happened, and the decisions that were made. But I hope that a big part of the lessons we learn that accompany any tragedy is that we can’t expect people to be perfect. And we shouldn’t design systems or structures that require them to be.

If this publication has been a source of wisdom for you then please consider helping me sustain it by becoming a monthly or annual contributor.

For just $8.00/month or $80.00/year, you'll help ensure I can continue dedicating more time to creating thoughtful, quality content. In fact, I’m currently sitting on over 200 draft articles (in various stages of development), which I just haven’t had time to publish. Of course, a third of those articles are probably crap, but that would still mean I’m sitting on tons of content I’d love to share.

As a sponsor, you’ll also be the first to receive future premium content, including a digital copy of my upcoming book, “The Proper Use of Shared Values.”

It’s completely optional and I’ll always provide as much content as I can for free, but your contributions will be critical for helping me spread the word about new ways of collaborating that are both more effective and more meaningful.

I agree here, that when you are operating within a system, a choice is never a purely moral or personal choice, but often influence by the system - at play - a boat, a natural environment or an organization.