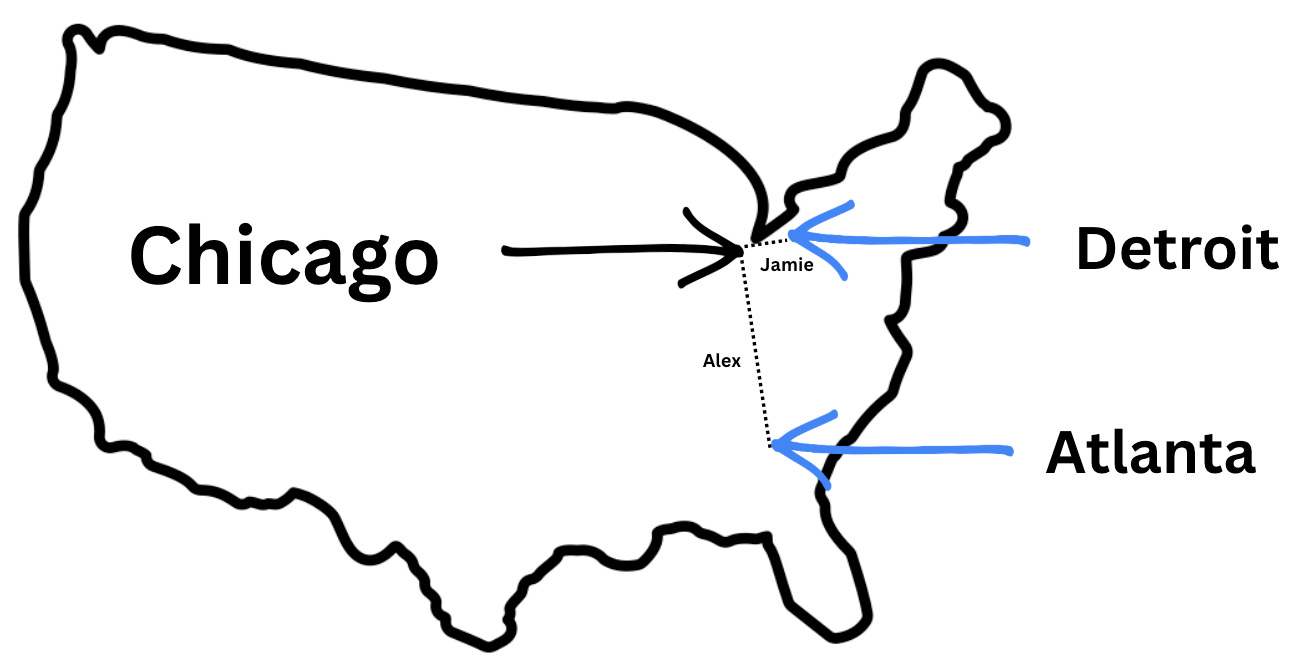

Meet Alex and Jamie. Both are leaving from the heart of Chicago, early on a Friday morning. Each is heading to visit an old friend for the weekend, but in opposite directions.

Each plans to leave their house at exactly 8:00 AM.

Alex is headed to Atlanta which is 700 miles away, and Jamie is headed to Detroit which is about 280 miles away.

So, here’s the question: in the real world, which trip do you think takes more time to complete?

The obvious answer would be that Alex’s trip takes longer because it’s further away (700 miles vs. 280 miles), but (and this is the key) if the scenario played out in real life, it’s likely Alex’s trip would take less time than Jamie’s.

Why? Because Alex would likely be flying on a plane (total trip time: ~5 hrs.), and Jamie would likely be driving a car (total trip time: ~5.5 hrs).

The point? We often misjudge how things will play out in reality when we think only in logical, abstract terms. Which of course is all we can do when we make predictions.

We’re Bad at Predicting

While we’re often really bad at knowing how things will unfold or how long something will take, we are especially bad at predicting how we’ll feel about something in the future.

Psychologists call the process of predicting our feeling “affective forecasting” and according to decades of research, we suck at it.

I got hip to this idea from Dan Gilbert when I was working as a research assistant in his psychology lab. He explained to us (and later elaborated in his book Stumbling on Happiness) that when people imagine future scenarios, they do so using the abstract, static facts they can think of in the moment, but this necessarily excludes lots of other data they would have if the situation were real.

So, for example, in one’s imagination, Atlanta just seems farther away than Detroit, so it must take longer. Just like a big life decision—starting a new job, moving cities, having kids—can feel emotionally huge and uncertain in advance. But when the time actually comes, we often handle it better than expected.

Take debilitating injury, for example. Gilbert found that people vastly overestimate how miserable they’ll feel after losing the use of their legs when compared to people who actually have.

When asked to predict their happiness a year after becoming paraplegic, most people imagine near-constant despair. But when Gilbert actually interviewed individuals who had experienced such injuries, they found that these individuals reported levels of happiness not so different from those who had never experienced such trauma.

The reason? Once people are actually in the situation, they adapt. They build new routines, shift priorities, reframe their circumstances. Their emotional system recalibrates.

But in the abstract, before any of that adaptation begins, the mind can't simulate that dynamic process—it can only conceive the crippling loss.

So we misjudge. Not necessarily because we’re irrational, but because our imagination lacks access to the mechanisms of coping, reframing, and engagement that only activate in context. And that’s the deeper point: the tools that help us navigate hard realities often don’t show up in our forecasts—but they do show up when we need them.

As Gilbert puts it, we are “more resilient than we realize,” and our minds are built to regain equilibrium faster than we anticipate.

Predict & Control

“Our anxiety does not come from thinking about the future, but from wanting to control it.” -Kahlil Gibran

So what do we take away from this? Well, it’s not necessarily that we need to feel better about the future, or even that we should trust ourselves more (though we probably should)—but that even trying to predict the future has serious limits.

Especially when it comes to how we’ll feel or perform, prediction is built upon a frozen and abstract version of reality. And Gilbert’s research doesn’t just expose a psychological quirk—it also reveals a structural problem that becomes embedded in most organizations: when we rely too much on planning from a distance, we miss what becomes possible once we’re actually engaged with real conditions.

But unlike individuals, organizations need to maintain alignment among many individual parts and the only way to do that is to have clear expectations. Of course, what are expectations, but a form of prediction.

So, organizations as well as individuals must do a certain amount of prediction: what will happen, how will I feel, and how can I prepare in advance? But most of our real capacity comes online when we’re in motion—when we can sense what’s happening here and now and adjust.

In that light, the trip to Atlanta at the beginning of this article wouldn’t take less time because it was predicted better—it would take less time because the actual way someone would get there in real life would make it so. But again, you wouldn’t see that just by looking at the map.

Likewise, in life, we often overestimate the usefulness of foresight and underestimate the value of good structures and real-time feedback. The smarter paradigm is “sense & respond”—it’s one that encourages us to build systems that allow us to adjust in motion, rather than ones that try to perfectly predict in advance.

If this publication has been a source of wisdom for you then please consider helping me sustain it by becoming a monthly or annual contributor.

For just $8.00/month or $80.00/year, you'll help ensure I can continue dedicating more time to creating thoughtful, quality content. In fact, I’m currently sitting on over 200 draft articles (in various stages of development), which I just haven’t had time to publish. Of course, a third of those articles are probably crap, but that would still mean I’m sitting on tons of content I’d love to share.

As a sponsor, you’ll also be the first to receive future premium content, including a digital copy of my upcoming book, “The Proper Use of Shared Values.”

It’s completely optional and I’ll always provide as much content as I can for free, but your contributions will be critical for helping me spread the word about new ways of collaborating that are both more effective and more meaningful.

Interestingly, companies tend to rely on predict and control because they are structurally conservative - not conservative in the political sense - but conservative in the sense that they always strive to continue to exist. Paradoxically, Predict and control paradigm is a very fragile way to ensure that - in the framing of Nicolas Taleb. You most ensure continuation by being anti fragile. Comes in Sense and Respond - which is much more anti fragile