Descriptive vs Prescriptive Expectations

Don't Confuse Observations for Obligations in Your Close Relationships

In our moment-to-moment experience, there is often little difference between what we expect will happen and what we think should happen. If the floor is wet…and a wet floor could cause someone to slip and fall, then, “it should be cleaned up.”

But in 1739, Scottish historian and philosopher David Hume argued there is a fundamental difference between statements about facts (what “is”) and statements about values or duties (what “ought” to be). And that you cannot derive an ought solely from an is without introducing some normative principle.

If we go back to the wet floor example, we don’t automatically arrive at the conclusion, “then I should clean it up,” unless we insert a normative principle like, “(and I don’t want people to fall)” into the equation.

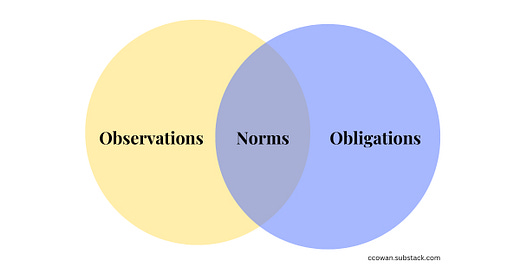

Observations and Obligations

But as I said, in our moment-to-moment experience this is rarely a meaningful distinction. Our minds integrate lots of data and perspectives, mostly outside of our direct awareness, to provide us a coherent experience of agency and reality. And so any short logical jumps made from is —> ought are perfectly justified.

Hume’s point wasn’t that this was inherently a problem to be eliminated, but simply to bring awareness to it (i.e. it’s not a problem to solve, but a problem to manage). That is, he isn’t saying we shouldn’t mistake is for ought, he is simply saying we do mistake is —> ought, which happens to be a good example of the utility of his distinction.

Said another way, we tend to conflate our observations (descriptive expectations) with our obligations (prescriptive expectations). This confusion plays out in a few ways:

Dawn, a new employee, observes that most employees take a lunch break at noon (descriptive) and mistakenly assumes it is required (prescriptive).

There is a workplace policy that states that employees should submit reports by Friday (prescriptive), but Frankie thinks this is just what most people do (descriptive), and so he doesn’t feel compelled to meet the deadline.

In each of these scenarios, the expectations themselves are pretty clear. It’s the type of expectation that’s getting mixed up.

And even though this confusion happens all the time, the difference rarely gets noticed (or even matters) because our expectations of each other generally get satisfied.

Norms = “Normal”

Normally, we don’t have to think very much about what’s normal. Different contexts and different scenarios have different rules that guide or shape behavior, but we tend to navigate those complexities, not as distinct elements that must be consciously woven together, but through a singular impression or sense of the overall situation (i.e. a gestalt).

In this way, we sense and respond to what is normal, even as situations change. We can get specific when we talk about norms, which are shared behaviors that guide behavior and interaction, which give our experience of the group some stability and predictability. For example, it’s normal for me to put my shoes in the shoe bin when I get home, and it doesn’t really matter whether there is a descriptive or prescriptive expectation behind it.

So, our expectations get operationalized into norms (both reflecting and reinforcing them), which means when conflicts arise, we can start by looking at the norms or our innate sense of what is “normal.”

But what happens when there is a problem? If we don’t have the distinction, then we can’t easily diagnose where the confusion took place or how to resolve it. And in that ambiguity, we usually resort to blaming the person, which makes things worse.

Why This Matters for Close Relationships

I first thought about why this is important for close relationships a few years ago when I revisited a rule in Holacracy®, “Implicit expectations hold no weight (4.1.5).” Even as a Certified Holacracy Master Coach, I thought it was an odd rule—or at least an odd way of saying it. Because clearly, people have lots of implicit expectations (i.e. observations) of each other that are perfectly valid to have. For me, I finally understood what the rule was trying to get at when I thought of the distinction between descriptive expectations. Here is how we can draw lines between them:

The distinction between observations and obligations helps explain why it can be awkward to ask a friend or family member for a favor, because on one hand, we can’t automatically expect them to do it, but we kinda expect them to do it.

Again, the difference between observations and obligations rarely gets noticed because expectations generally get satisfied. The point isn’t to artificially label our expectations unnecessarily, but simply to have a mental model ready to go when things go wrong.

Understanding a Failed Expectation

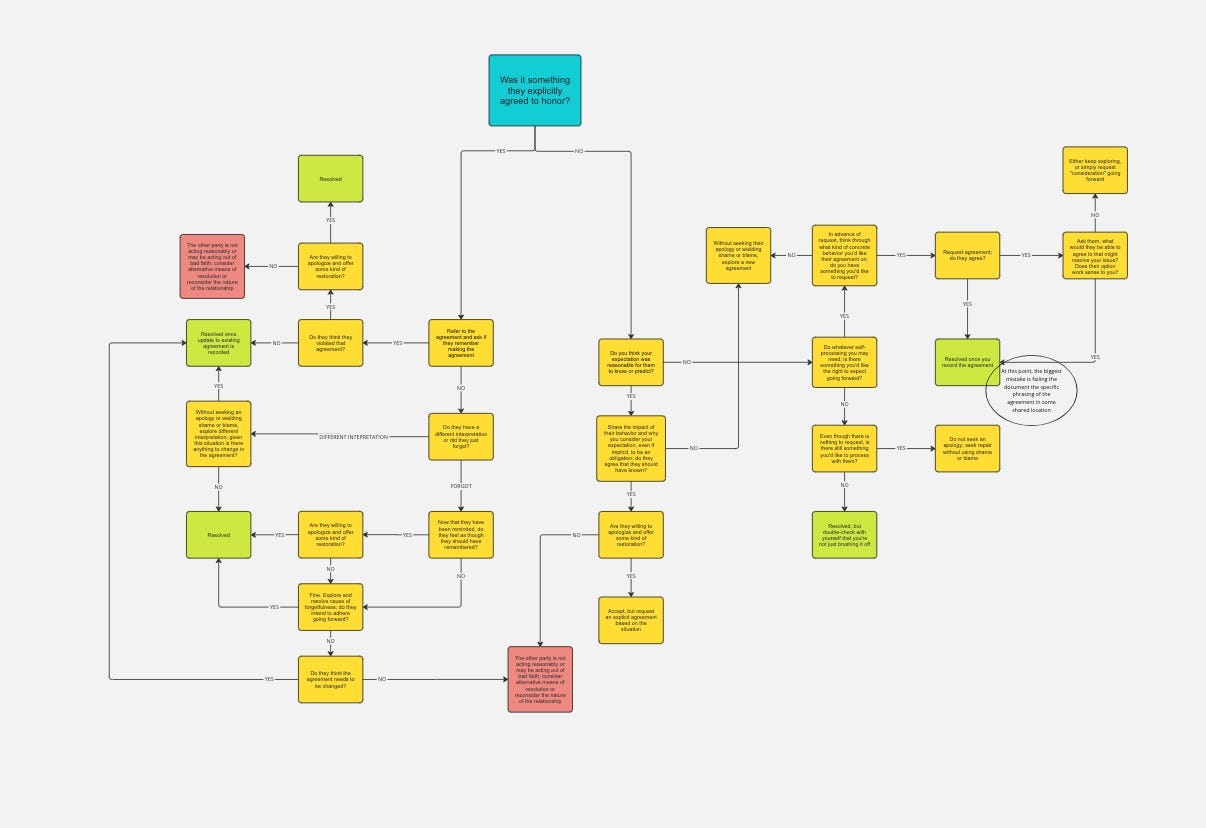

With the distinction clearly defined, now we can actually get to the good stuff—how to use it. For me, “What do I do when someone fails to meet an expectation I have?” is probably the most interesting inquiry to have. In large part, this whole conceptual model, as I present it here, is based on this question alone. So, let’s first look at an example:

As you can see, the ways in which Amy and others behave in response to the failed expectation are completely dependent upon the type of expectation; descriptive or prescriptive. Not only are they dependent, but they are also understandable and even predictable once we know whether or not there was an explicit expectation or agreement made.

All of this means that when someone fails to meet one of your expectations, you must first ask the question: “Was it something they explicitly agreed to honor?” Your answer to that question determines a lot. For those interested, I developed a decision-tree Miro board which walks through the logic, but either way I recommend skipping it for now and coming back after finishing the article, because the next short section on defining expectations is equally important.

Conclusion

We should try to remember is ≠ ought is any analysis. The way things are now and the way things should be are actually two very different perspectives.

In our defense, the distinction between observations and obligations is sneaky. Not only is it nuanced, but it doesn’t become an issue until it creates tension for someone. The real problems begin when someone fails to meet an expectation. Disappointment. Confusion. Frustration. Either side may feel mistreated. Often both. Simultaneously.

Therefore, when other people don’t align with our implicit standards (i.e. what should be), let’s first remember to face the reality (i.e. what is) with some patience and understanding—especially for yourself.

But equally, let’s not let our standards weaken too early, unnoticed, under the weight of our concern for how others feel. If they did make an explicit agreement, and they failed to live up to it, then maybe it’s their behavior that needs updating, not your expectations.

But Don’t Take My Word for It:

When a measure becomes a target it ceases to become a good measure. -Goodhart’s Law

A wise man sees as much as he ought, not as much as he can. -Michel Montaigne

We are much beholden to Machiavel and others; that write what men do, and not what they ought to do. -Francis Bacon

The traveler sees what he sees, the tourist sees what he has come to see. -Gilbert K. Chesterton

The ability to observe without evaluating is the highest form of intelligence. -J. Krishnamurti

Man is the only animal that laughs and weeps; for he is the only animal that is struck with the difference between what things are, and what they ought to be. -William Hazlitt